Research

Published 21 September 2023Ancient indicators of inequality

Bioarcheologist Professor Siân Halcrow from Te Whare Wānanga o Ōtākou University of Otago has recently concluded a significant Marsden funded study into some of the earliest forms of social inequality, emerging from Bronze Age China.

The rise of social inequality played a critical role in the development of state-level societies throughout the world, resulting in detrimental impacts on marginalized social groups. The legacy of this has major repercussions on society today, including the health of women and children. To understand this historical development, Professor Halcrow (Principal Investigator) and her team of Associate Investigators from Aotearoa New Zealand, China, and the USA explored the emergence of gender based inequity in the rise of Bronze Age China (Eastern Zhou) in the Central Plains region (771-221 BCE). The team examined multiple skeletal tissues in cemetery populations to demonstrate how social inequality impacted on health and nutrition over the life-course. Their findings show that the treatment of mothers has detrimental effects on both boys’ and girls’ development, and that girls are gendered through being fed less nutritious and less culturally valued food.

A main focus of the project carried out by Dr Melanie Miller (University of Otago / University of California, Berkeley) and Dr Dong YU (Shandong University) was investigating relationships between food and gender in early life by studying childhood diets. Using chemical (stable isotope) analysis of dentine incrementally over tooth growth, detailed childhood dietary histories were constructed, with findings showing dietary differences between males and females. These patterns began in early childhood, with males eating more valued grain (millet) and more meat, while females consumed more of the less valued wheat and soybean. Halcrow and her team believe that certain foods were associated with aspects of gender, such as meat and masculinity. These insights reveal a key aspect of the socializing processes of children across generational interactions with their caretakers, whereby food represents and communicates values about gender, which becomes embodied in the developing child (Halcrow et al. 2022; Miller et al. 2021; Miller et al. 2023 in press).

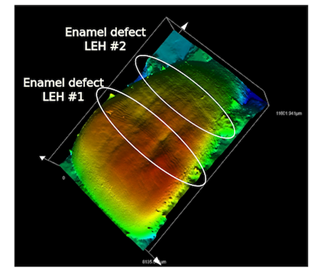

Skeletal and dental remains indicate changes in a person’s environment and can encode sex-based differences in types of stress experienced from nutrition and/or infection, including dental enamel defects. Master’s student Sunday De Joux undertook a detailed analysis of dental defects from three Eastern Zhou sites, using a new method to assess if there were significant negative deviations on a digitized cross-section of the tooth surface (figure).

Figure 1: Example of a scanned upper central incisor tooth. The high-resolution scan shows 2 dental enamel defects called linear enamel hypoplasias (LEH). The location of these defects can be estimated to a particular period of dental development. The co-occurrence of LEH defects across multiple teeth with overlapping developmental chronologies is an indicator of a systemic stress event an individual experienced during that specific period of early life.

She found that all individuals had encountered at least one event of stress on their health (such as disease or famine), with no sex-based differences. These results are interesting, given that historical and archaeological research tells us that female health was negatively impacted by the effects of a heavily male dominated society and resulted in male-biased differences in both child-rearing and social status. A reason for why sex differences are not observed, Halcrow and her team argue, is because enamel defects develop in infancy and early childhood, and therefore reflect maternal stress.

With such insights into gender-based differences in diet and cultural treatment during the Eastern Zhou, focus now turns to the ways gender ‘intersects’ with class, disadvantaging individuals further. This expanding research direction involves Ms Qian Zhang — a visiting student from Shandong University. The newly excavated cemetery site of Dahan (大韩) in Shandong provides an opportunity to investigate the intersectional nature of gender, class, and diet and health, with evidence for noble people being buried with companion (sacrificial) burials. There are status-based dietary differences in this cemetery, with nobles consuming more high-protein foods and more valued staple foods (mainly millet) compared with companion human burials, and gender-based differences in diet being specific to class, showing the importance of understanding the intersectional nature of gender (Zhang et al. in review).

RESEARCHER

Professor Siân Halcrow

ORGANISATION

Te Whare Wānanga o Ōtākou University of Otago

FUNDING SUPPORT

Marsden Fund

CONTRACT OR PROJECT ID

UOO1823 - Small beginnings, significant outcomes: A new life-course approach to understanding the impacts of social inequality on human health in ancient China