Research

Published 28 February 2022Can a virtual uterus help us detect problems in pregnancy?

In this Marsden-funded project, Associate Professors Alys Clark and Jo James from the University of Auckland are developing a ‘virtual uterus’ to test ideas about what makes a healthy pregnancy, giving more pēpi (babies) a healthy start to life

The whare tangata (uterus) plays a crucial role in pregnancy, delivering nutrient-rich blood to the surface of the placenta to feed the growing pēpi. The way the blood vessels in the uterus adapt to pregnancy is remarkable, enabling it to carry 15 times more blood at the end of pregnancy than at the start. To do this, many blood vessels in the uterus double in diameter and some have their structure completely changed by placental cells that invade into the uterine wall. Unfortunately, in some pregnancies this transformation does not happen as well as it should, restricting maternal nutrient and oxygen delivery to the fetus.

One complication of pregnancy is fetal growth restriction, where the pēpi does not grow as well as it should. This condition can lead to increased risk of life-long health problems including heart disease, and in the worst cases, stillbirth. Concerningly, more than half of growth restricted pēpi are not detected prior to delivery, and we cannot identify which pregnancies are at risk in early pregnancy. This is the time when the most extensive changes in the uterine blood supply occur, and when simple drugs, such as aspirin, may help improve outcomes.

We know remarkably little about how the uterus adapts to pregnancy, and detecting problems with how the uterus delivers nutrients to the pēpi is difficult. Most differences between a healthy and not-so-healthy pregnancy are microscopic, so the mainstay of clinical assessment of pregnancy –ultrasound – can miss the early signs of problems in growth. Invasive procedures are avoided in pregnancy, meaning that the pregnant uterus is largely inaccessible for clinical studies.

So, how can we improve our knowledge of pregnancy and fetal health in a safe, non-invasive way? In this Marsden-funded project, Associate Professors Alys Clark and Jo James are developing a ‘virtual uterus’ that will allow researchers to investigate what makes a healthy pregnancy, what happens when blood vessels in the uterus fail to adapt to pregnancy and where in the uterus the most important changes occur.

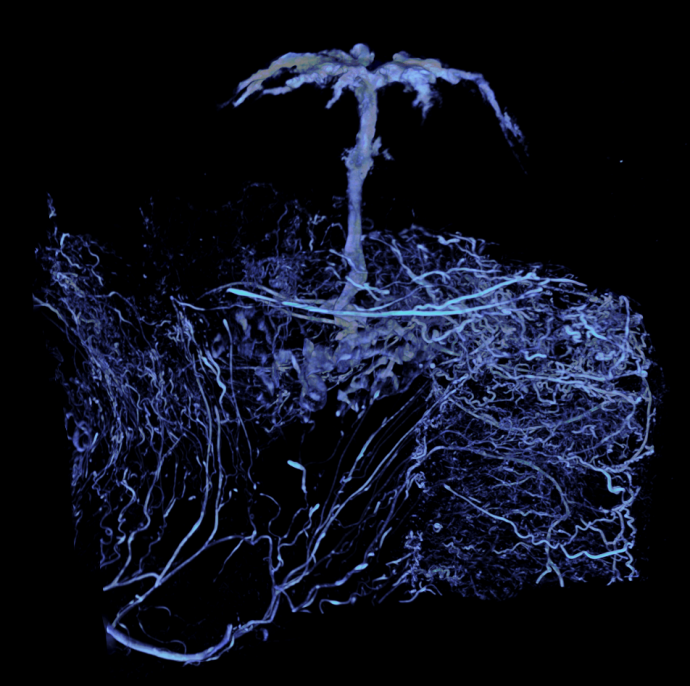

Left: This is an image of the blood vessel network of a rodent uterus captured by micro CT. Middle: Precise 3D details can be extracted using computer-based analysis. Here the researchers reveal arteries feeding a single placenta, the organ feeding the fetus. Right: These precise details are then used to recreate a ‘virtual’ uterus. Images: Supplied.

Working with researchers in the UK, Australia and New Zealand, Clark and James are bringing together the latest advances in physiology, bioengineering and computer modelling to develop the virtual uterus. Clark and her colleagues will reconstruct for human pregnancy structures similar to those shown in the trio of images above. At left is an image of the blood vessel network of a rodent uterus captured by micro CT, a technique similar to a CAT scan but of much higher-resolution. Nutrient-rich blood is transported to the placenta, which appears as the ‘tree-like’ structure at the top of the image. While micro CT is powerful, it does not allow researchers to study the function or interaction of individual vessels. Precise 3D details can be extracted using computer-based analysis. Here, the researchers reveal arteries feeding a single placenta, the organ feeding the fetus (middle). These precise details (right) are then used to recreate a ‘virtual’ uterus where the team can begin to test ideas about function and dysfunction.

Clark and colleagues already have prior experience in this area, having created a world-leading ‘virtual lung’ for which they and colleagues received the 2018 University of Auckland Research Excellence Medal.

The new knowledge generated from this project are the vital first steps towards improving the detection of fetal growth restriction and will give more pēpi a healthy start to life.

RESEARCHER

Alys Clark

ORGANISATION

University of Auckland

FUNDING SUPPORT

Marsden Fund

CONTRACT OR PROJECT ID

UOA1815 - 'Feeding your baby in utero: Which arteries matter?'