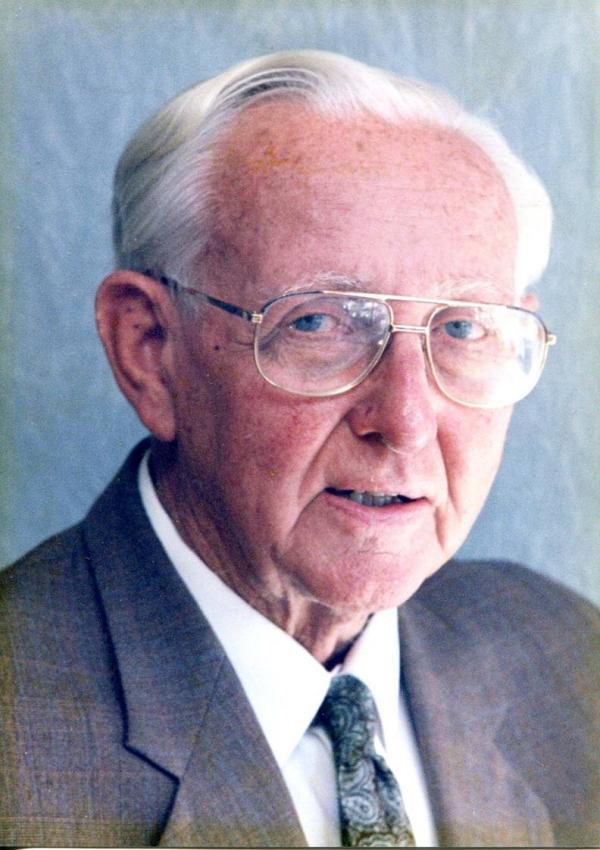

Edward George Bollard

(1920–2011)

CBE BSc NZ PhD Cantab HonDSc Auckland Hon FNZIC FRSNZ

Edward G Bollard FRSNZ

Ted was one of the giants of our small science system … Ted argued for the essential value of science for New Zealand’s development. Indeed his research in plant science has had a major legacy, particularly within our horticultural sector.

Sir Peter Gluckman 2011

His personal research and involvement in science at a national and international level ensured that Bollard, like so many of his generation, was intimately involved in positioning horticulture as one of New Zealand’s foremost ‘knowledge-based’ industries and [as] a powerful competitor on the world stage. This legacy lasts to this day.

Professor Willie Smith 2008

Early life and education

Ted Bollard was born on 21 January 1920 in Athlone, Ireland. Athlone was then a small town of less than 10,000, situated close to the geographic centre of Ireland on the banks of the river Shannon near the southern shore of Lough Ree. Ted was one of three children by his father’s second marriage. His father, Edward, held a responsible position as a civil servant eventually becoming deputy Head of the Athlone Post Office. His mother had trained as a nurse. The family was Protestant, but the population of Athlone was overwhelmingly Roman Catholic and only 3% of the population was Protestant. The family lived in a large stone house in the main street of Athlone; relatives had farms and their lifestyle could be described as established lower middle class. This comfortable life was threatened by the creation of the Irish Free State in 1921. Athlone had been a garrison town for the British Army but the Army of the Irish Free State took over. Ted’s father believed that as a Protestant, he had few prospects for advancement with the new Irish government and he also felt threatened by the proposed introduction of Gaelic. The family believed that as loyal subjects they had been betrayed by British politicians such as Lloyd George. Emigration was considered, with the options being Canada and New Zealand as Ted’s mother had married sisters in both. New Zealand was chosen, partly because the then Minister of Internal Affairs was a Richard Bollard, of Irish descent, even though a family relationship could not be established.

The family left Athlone in September 1929 and arrived in Auckland in November of that year. The following year, his parents bought a 12-acre farm in Glen Eden, similar to the farm on which his mother had been brought up in Ireland. Glen Eden is now a suburb of west Auckland but was then lightly settled in mixed farming and horticultural use. His parents’ dream of farming proved to be unrealistic, especially as the Depression set in. His father was unable to get a job of a status similar to that which he had enjoyed in Ireland, although he was helped by a pension he received from the Post Office in Britain. Life in New Zealand was difficult and did not come up to expectations – certainly, when Ted looked back his memories were of poverty and of the extreme financial pressures that his parents faced. This as he put it,

- …left me with strong ideas of control of expenditure in the home (some people assert that I am mean). I hate throwing anything away, whether clothing or equipment.

His notoriously crabbed handwriting, the despair of many typists, was, he claimed, due to the single sheets of paper then handed out to pupils each morning and afternoon at primary school.

Ted had started at the only Protestant school in Athlone from the age of six. By then he could already read and was able to do some arithmetic. In Auckland he attended the New Lynn and Glen Eden Primary Schools and then from 1934 to 1938 he was at Mt Albert Grammar. He travelled in by train from Glen Eden each day. As the family circumstances were straitened he had to get up before 6 a.m. each day to undertake a New Zealand Herald delivery run before having a rushed breakfast and catching the 7.50 a.m. train, a schedule he grew to hate. He was not good at languages, but instead enrolled in what was called the Science Course in which Biology replaced Latin in an otherwise standard course. This set him on his future career path and it was in this class that he first met Dick (R. E. F.) Matthews who was to become one of his closest friends.

In 1938, Ted was Dux of the school. He remained very appreciative of the education he had received, particularly for introducing him to Shakespeare – something that remained a lifelong fascination – and to more contemporary writers such as Dorothy Sayers, John Buchan and Rafael Sabatini. In notes left with the Royal Society of New Zealand, he said that he was inspired and much influenced by two of his science teachers, W. Caradus and M. J. O’Sullivan. He was also grateful to the headmaster, F. W. Gamble, who apparently persuaded Ted’s mother that he should not be forced to leave school because of the need to earn money to support the family. In 2004 Ted was inducted as a member of the Hall of Distinction of Mt Albert Grammar.

In 1939 Ted went to Auckland University College and enrolled in a science degree. Amongst other lifelong friends that he first met at university were Dick (R. K.) Dell and Eric (E.G.) Godley. Two of the staff who particularly influenced him during his university years were T. L. Lancaster of the Botany Department and Professor L. H. Briggs of the Chemistry Department. In December 1940, after completing his second year at University (but with one paper to finish his degree), he wrote to Dr Gordon (G. H.) Cunningham, Director of Plant Diseases Division (PDD), Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR), Mt Albert, seeking employment. He was immediately appointed to a temporary position to assist Ken (K. M.) Harrow on timber preservation. The headquarters of PDD, the first government building constructed after the depression, were just over the fence from Mt Albert Grammar and Dick Matthews was appointed to the staff the same year.

The Army

In 1940, Ted and a number of other second-year degree students volunteered for the Territorial Force. The Corps of Signals was seeking recruits with university training. This meant weekly evening instruction and an annual camp of three months. 1941 proved to be a very broken year for Ted: the first three months were spent in intensive training at Trentham Military Camp; next he was in hospital or recuperating from appendicitis; and then he was studying to complete his degree. He had just recommenced full time work at DSIR in December when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. All Territorial units were immediately mobilised.

Ted served continuously in the New Zealand army for five and a half years, in New Zealand for 2 years and 263 days and overseas for 2 years and 266 days. He did not return to Mt Albert until 1948.

He was initially posted to Kaikohe where the headquarters of the 12th Army Brigade were being assembled. There they had to construct their “cookhouse” and a “mess room” from trees growing in a nearby swamp, the sides of the buildings being covered with raupo, also harvested from nearby swamps He had expected to be posted overseas in 1942, but the despatch of reinforcements to the Middle East was delayed and he was to spend the next fourteen months at Kaikohe, a period he described as:

- …the most boring period of my life; the fourteen months there were personally a wasted period.

Being a signaller required proficiency in Morse code. Ted eventually achieved an output of 20 words a minute, an ability he retained late in life. He rose through the ranks to become sergeant and this:

- …entitled me to carry a revolver and have a motor bike. I had a great big Indian bike – American style with a hand gear change and many other features.

In February 1943 Ted was transferred to Trentham Camp as a preliminary to his departure to the Middle East as a member of the 9th Reinforcements of the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (#279690). On 14 May 1943 he left for Suez on the Dominion Monarch, which had been modified to carry over 4000 troops. For most of his life, after leaving school, Ted kept a daily diary. He continued this, during training in Egypt and then during the invasion of Italy and the subsequent fighting. Apparently unexpurgated, typed transcripts of this war-time diary have been deposited in the Alexander Turnbull Library and in the Waiouru National Army Museum. He also wrote short essays or “jottings” on some of his other army experiences. His diary reveals the utter boredom of much of army life; the routines such as the constant washing of clothes; the cold; the tiredness and sometimes exhaustion; the medical misadventures such as dysentery, jaundice, scabies and lice; and the exposure to real action.

- You slowly got used to all the noise but at night when we were trying to sleep in open slit trenches… I felt lonely and on my own. It would be wrong to say you were not frightened but you could not do anything about the situation you found yourself in. We did get used to this type of situation very quickly and by the time of our major attack a few days later our whole attitude had changed. Don’t get me wrong –you never got completely happy with incoming shell fire but you have to distinguish between the really dangerous shells and those you can afford to ignore.

Late in life he admitted,

- I still think and dream about those days.

For six months, Ted was posted as a brigade signaller - one of only two pakeha - to the Maori Battalion, a very experienced unit. He was in heavy action in the long drawn-out battle for Cassino, fighting through the ruins, and he thought he was the first New Zealander to climb the hill after the battle and walk through the remains of the Benedictine monastery of Montecassino. It was revealing to observe Ted in later life at functions when senior Maori figures were present. There was a special bond, because he knew many of them personally as a result of their joint war time experiences.

Several other PDD staff were also in the army and in his diary he mentions meeting Torchy (J. D.) Atkinson), Ted (E. E.) Chamberlain, Harold (H. M.) Mouat and Frank (F. J.) Newhook. Even more important were his frequent meetings with two of his closest friends, Dick Matthews and Eric Godley, in Egypt and then in Italy:

- Surprising news that Dick and Eric are over here. Frank [Newhook] and I drove out to camp at Mena and met them – great reunion. (Diary, 19 August 1943)

- In Cairo with Dick and Eric for last time. (Diary, 17 September 1943)

- and the next day… Suffering from hangover from last night. (Diary, 18 September 1943)

- Six months later: After lunch set off to look up Dick and Eric. Hitch-hiked back about 5–6 miles and found them both in the same area. Both of them glad to see me safe, etc. Had very enjoyable afternoon recounting experiences, etc. Realising more and more what good friends I have in these two and how similarly our minds work. (Diary, 24 March 1944)

After Cassino came Faenza and then Ted ended his war at Aurisina, near Trieste, which was then very much under threat from Tito’s Partisan forces. The end of the war in Europe seems to have been almost an anti-climax:

- Listened to Churchill’s broadcast announcing the official end of the war – hostilities to cease at one minute past midnight tonight. Surprisingly little excitement. (8 May 1945)

The summer at Aurisina was wonderful and peaceful with lots of swimming, sightseeing trips and dances with the local girls. One of these exchanged letters with Ted for the next 50 years.

Cambridge

Home called, but instead came the possibility of postgraduate study. The Prime Minister, Peter Fraser, had addressed the New Zealand troops in Italy and various schemes were introduced to encourage the rehabilitation of servicemen. Some were enabled to go direct to British universities rather than return home, which, as Ted noted:

- …was not only the exception at that time, but was an opportunity which would not have been available under pre-war conditions.

Dick Matthews had gone to Cambridge and then came the opportunity for Ted.

- News that Dr Chamberlain has been in communication with Dad re my going to England before going home in order to study there possibly even at Cambridge. This is really good news and I am quite surprised. (Diary, 3 August 1945)

- Received a significant letter from Dick [Matthews] – Chamberlain has told him that Ham [Dr Cunningham] wants me to go to Cambridge. (Diary, 5 August 1945)

- Just before lunch the long expected letter from E.E.C. [Chamberlain] and also a testimonial from G.H.C. [Cunningham]. He wants me to do research in Field Mycology – very satisfactory indeed. (Diary, 20 August 1945)

On 5 October came the official letter confirming that he had been awarded a bursary. Ted arrived in Cambridge on 20 October to join Dick Matthews at Emmanuel College; Eric Godley came a few weeks later to Trinity and Alan (A. T.) Johns was at Clare. They were sometimes known as “the four musketeers”. All four were later to become Fellows of the Royal Society of New Zealand and to achieve very senior positions in New Zealand science: Ted himself was Director of a DSIR Division, President of the Royal Society of New Zealand and Pro-Chancellor of the University of Auckland; Matthews became Professor of Microbiology at the University of Auckland; Godley became Director of Botany Division, DSIR and Johns became first Director of Plant Chemistry Division, DSIR, and then Director-General of Agriculture, Pro-Chancellor of Massey University and Chairman of the University Grants Committee.

Life in the “cloistered courts” of Cambridge was a challenge after life in the army.

- …you tended to miss your army associates, who had always been close around. Food rationing was a problem – you had to hand over to the college your entire ration book. Rooms were not heated – you had an open grate and a small ration of coal and fire lighters.

In the last page of his war diary, Ted noted the meagre amounts of food at his first college dinner. Worse, the main course was often fish, something he refused to eat, no matter how hungry. Tea was provided only at breakfast and otherwise the ration was half a pound (220 g) per month.

After a year in college, Ted, Godley and Matthews rented accommodation from Frances Cornford, a poet, friend of Rupert Brooke, granddaughter of Charles Darwin, and mother of the communist poet John Cornford - who was a friend of Anthony Blunt. This was high Cambridge academia. They had planned that Dick Matthews’ mother would housekeep for them, but she became ill and had to return to New Zealand. They then moved into an upstairs flat in Cambridge with Alan Johns and his family on the floor below. Food parcels from New Zealand provided an essential supplement to their diet – it was also helpful that Dick Matthews’ experimental studies required growing large quantities of potatoes.

Ted undertook PhD studies at the Botany School under Professor F. T. Brooks, as arranged by Dr Cunningham. Brooks was about to retire as Head of the Botany School. Although he had built up an outstanding centre of research in mycology and plant pathology he was, as described by Sir Harry Godwin, “unpredictable and choleric” with distinctly paranoid tendencies. Brooks was not the ideal supervisor for one nearly 40 years younger and Ted believed that he had taught Brooks more than he had learnt from him. Ted also attended undergraduate courses because there was much to catch up – he had been away from science for more than four years. He particularly remembered lectures on statistics from Fisher himself. From his thesis, Ted published two papers on the genus Mastigosporum, a fungus which causes leaf spot disease of grasses. This experience of plant pathology helped him when he later became Director of PDD.

DSIR and Mt Albert

Ted graduated in June 1948 and then returned to New Zealand and to Mt Albert. The relatively large number of returning servicemen appointed as scientists formed an egalitarian cohort of friends and acquaintances of similar age that was to form the research base of New Zealand for the next generation. Ted was appointed to DSIR and he was soon in the Fruit Research Station (later Division), split off from PDD and led by the new Director, Torchy Atkinson. The Depression and the War had prevented any expansion of scientific research in New Zealand. After the war, research still developed slowly because funds were very scarce. Laboratories were crowded, facilities were poor, as were the salaries. The returning scientists starting families were hard pressed financially. In 1951–52, to supplement their salaries, Matthews, Newhook and Ted rented a 5-acre (2 ha) block in Owairaka Avenue, Mt Albert, then still farmland, and grew a variety of crops, the most successful being beans and kumaras. By working hard each weekend, they managed to clear £70 each in the year – a sum they considered inadequate for the effort required.

In some unpublished “jottings”, Ted summarised the way in which DSIR then operated:

- The DSIR approach to the delivery of scientific discovery to end users was to encourage close communication between scientists and industry organizations. For the rural sectors this meant that scientists were encouraged to consult with the Ministry of Agriculture advisors and with growers, and then develop research programmes aimed to deliver results that could be practically applied at the earliest possible stage. The policy was liberal and flexible, it being accepted that where no immediate and obvious solution to a problem was available, then scientists were free to attempt indirect attempts on a problem by doing research on the underlying questions; of doing basic science. Most scientists understood and accepted this policy and for the most part it efficiently produced practical end results.

Ted clearly believed in this approach and he often complained of the comments made in ignorance much later by people who had unrealistic ideas of what research involved and how it should be managed:

- People of my generation consider it absurd to hear that in the past priorities were not really sorted out, that work was not coordinated and that many scientists did not feel accountable for their work.

He was appointed to DSIR as a plant physiologist. Earlier, the remarkable success of Torchy Atkinson in establishing that corky pit or internal cork of apples was due to a deficiency of boron and that the disorder could readily be overcome by application of borate, led to the idea that a number of unsolved syndromes in fruit trees might be mineral deficiencies or other physiological inadequacies. If it could not be established that a fungus, bacterium or virus was involved, then the easy solution was to believe that the cause was physiological. Often this was not the case and Ted’s pathology training quickly allowed him to show that collar rot of apples was instead caused by Phytophthora cactorum and blast of stonefruit by Pseudomonas syringae. However, in other cases the cause really was a nutrient deficiency. In a series of papers culminating in a comprehensive DSIR Bulletin, he recorded deficiencies of boron, manganese and zinc affecting fruit crops in many different parts of the country. Correction of the deficiencies was usually straightforward.

Another major effort of those early years was the preparation of the DSIR Bulletin, The Appleby Experiments, which wasfinally published in 1959. The Appleby Experiments, which were started long before Ted joined DSIR, were a classic series of apple tree fertiliser trials lasting some three decades at an orchard at Appleby, near Nelson. Because most of the fruit produced in the district were exported, the aim was to study the effects of nutrients not only on the growth and cropping of the trees but also on the quality of the fruit, particularly after storage. Three nutrients were applied in various combinations--nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium--using six different apple cultivars then widely grown. Contrary to what was expected from studies elsewhere in the world, the critical elements under the conditions at Appleby proved to be nitrogen and phosphorus, not potassium. This finding led to improvements in orchard fertiliser practice and it also stimulated much of the physiological work undertaken over the next decades at Mt Albert to understand what happened to minerals inside the plant. Phosphorus nutritional status affected the subsequent storage of the fruit, with high phosphorus content equating to small cell size and increased storage life. The implications of this were to be investigated by Rod (R. L.) Bieleski in his detailed studies of the phosphorus metabolism of plants. An interest in cell size and hence cell division led to the investigation of the stimulants of cell division that could be extracted from rapidly growing young fruitlets. This work carried on by Stuart (D. S.) Letham resulted in the isolation and structural identification of zeatin, the first naturally occurring plant cytokinin to be successfully characterised. Ted himself concentrated on nitrogen because excess nitrogen adversely affected storage quality of the apples.

At that time, it was generally believed that nitrogen moved through the xylem in inorganic form, but in 1953 in a letter to Nature (even then considered as the ultimate place in which to publish) Ted showed that in apple trees, most nitrate assimilation seems to occur in the roots and that nitrogen ascends in the xylem in organic form, as amino acids and amides. This was revealed by paper chromatographic analysis of the xylem sap extracted under vacuum. The work on nitrogen in xylem sap was extended to studies of other plant species to show that the presence of organic nitrogenous compounds in xylem sap was not just a peculiarity of apple trees. Aspartic acid and glutamic acid, and glutamine and asparagine, were generally the major nitrogenous constituents, but in some plants citrulline, allantoin and allantoic acid were important. These studies are the most novel and important of Ted’s contributions to plant physiology. Later, others in the laboratory used the same technique of xylem sap collection to study other problems: Ross (A. R.) Ferguson made a comparison of bleeding sap and vacuum-extracted xylem sap in kiwifruit and Ian (I. B.) Ferguson studied the movement of calcium in woody stems.

In 1956, Ted was awarded a Harkness Fellowship to work at Cornell University for a year. Opportunities to work in the United States were then rare, the Fellowship was reasonably generous and his DSIR salary would continue. However, families were not allowed to accompany the Fellow and this meant leaving a wife and three children, then aged 7, 5 and 3, back at home for more than a year. It was a tough decision to go, especially as the family finances were shaky. Ted recalled that when he left for the United States, the family had £5 in the bank. This was long before the days of international phone calls and he managed during his time away to phone home only once by radio telephone, not very successfully. The time at Cornell with Professor F. C. Steward, one of the grand old men of plant physiology, was successful scientifically, but perhaps more important it reassured Ted that the techniques they were using and the work undertaken at Mt Albert was as good as and sometimes better than those at a leading United States university. This was confirmed a few years later when Stuart Letham beat F. C. Steward in the race to isolate the first naturally occurring plant cell division factor, zeatin.

An unexpected bonus from the time in the United States was the acquisition of cultures of Spirodela oligorrhiza. This was a duckweed then being grown under sterile conditions by K. V. Thimann of The Biological Laboratories, Harvard University and Ted immediately recognised its potential. Cultures were successfully imported and at Mt Albert it soon became the plant equivalent of the laboratory white mouse. Spirodela was grown in liquid culture and this meant that the uptake of nutrients from the medium could be followed without the serious complications caused by soil or contaminating bacteria or fungi. Spirodela was used in studies with colleagues on the use of organic nitrogenous compounds as sole sources of nitrogen, the metabolism of supplied urea, and the induction of nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase and urease activity. This work provided some of the first clear examples of enzyme induction or activation in plants. Spirodela was also used extensively by Rod Bieleski and several students in studies on phosphorus metabolism.

Ted’s last nutritional studies centred on calcium, largely because localised deficiencies of this element seemed to be responsible for fruit disorders such as bitter pit in apples. He started by investigating the problems of fractionating tissue calcium in an attempt to resolve the difficulties caused by the sequestration of calcium as calcium oxalate. These studies were later extended as part of Ian Ferguson’s more detailed studies of calcium mobility in plants.

Ted built up a very comprehensive collection of reprints in plant nutrition in general and he read widely and extraordinarily systematically. A notebook covering the decade 1973–1983 shows that he checked each individual issue of nearly 150 periodicals that either were held by the DSIR Mt Albert Library or were passing through on circulation. This period covered his tenure as Director, with a consequent heavy administrative load; very few scientific managers of today would read extensively let alone even attempt to keep up with the literature in this way. Often he would notice before the librarians that a subscription had lapsed or an individual issue had not arrived. He used this knowledge of the literature to write a series of reviews. He had an ability to synthesise and to be able to draw conclusions and generalisations often missed by the individual authors. A good example is his chapter on the physiology and nutrition of developing fruits in The Biochemistry of Fruits and their Products of 1970. Two reviewers, Miklos Faust and G. A. D. Jackson, described this chapter as being respectively “clearly outstanding” and “of outstanding merit”, with Jackson commenting that the reader might “profitably begin with this section.” Ted was to be author or co-author of six major reviews and two DSIR Bulletins.

The “Barn” at Mt Albert

The years at the “Barn” at Mt Albert were probably the most satisfying scientifically of Ted’s career. Space in the existing buildings at PDD was very limited, laboratory space was required but approval of new buildings to Ministry of Works’ standards was not possible. The solution in 1952 was to get the PDD carpenters to construct a building, without a proper building permit, allegedly to provide room for the storage of the farm equipment. Tractors and mowers did occupy the basement, but the upper story became laboratory space and the loft a store for glassware and chemicals because in those days there was but a single yearly order placed for laboratory supplies obtained from overseas.

In one corner, there was a tiny office for Ted, lined floor to ceiling with boxes and boxes of reprints, thus leaving hardly any room for a visitor. At the other end was a similar office for Rod (R. L.) Bieleski which he shared at times with students, Dick (A. R.) Bellamy, Ross Ferguson and Mike (M. S.) Reid. Along the corridor were Ron (R. M.) Davison, Stuart Letham, Robin (R. E.) Mitchell and Harry Young.

The laboratory was managed by Ted’s long-time technician, Noel (N. A.) Turner, who became highly skilled in plant analysis and then paper and thin-layer chromatography. Noel played a very important part in Ted’s research programme and he trained many of the newcomers to the laboratory. There were visitors from overseas such as Professor Roy (R. E.) Young from the University of California, Dr Dennis (D. G.) Hill-Cottingham from Long Ashton Research Station and Dr Tony (A. R.) Cook, later of the Rowett Research Institute in Scotland. Slightly later came other students, Ian Ferguson and Ross (R. E.) Beever. Also in the laboratory was Rod Bieleski’s then technician Robert (R. J.) Redgwell, who soon earned the right of automatic precedence to spend the first half hour of each Monday morning conducting with Ted a post-mortem of the weekend’s rugby.

Linked to the Barn by an overhead bridge and a steep flight of stairs was a wartime Nissen hut, which periodically leaked or flooded, and other temporary buildings which housed the Department of Microbiology when Dick Matthews transferred from PDD to the University of Auckland. Here were the other staff who had also transferred to the University or had joined the expanding Microbiology Department. These included Peter (P. L.) Bergquist, Ray (R. K.) Ralph, John Marbrook, Stan Bullivant and students such as Bruce (B. C.) Baguley and Jim (J. D.) Watson. In all, the “Barn” and the Nissen hut contained an extraordinary concentration of talent and scientific achievement for a few years, with thirteen eventually becoming Fellows and one an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand.

Administration and science policy

Ted was appointed Director of PDD following the retirement of Dr Atkinson. He took the job with a certain reluctance because he knew it would mark the end of his involvement in “real” science. He had already proved his ability as an administrator while de facto Assistant Director for Dr Atkinson and he had been largely responsible for the detailed planning and liaising with architects and contractors about the then new Hamilton Building at Mt Albert. Ted remained with PDD until 1980 when he was appointed Director of the newly formed Division of Horticulture and Processing, largely a reincarnation of the old Fruit Research Division.

Ted retired in 1980 when he reached 60, then the compulsory retirement age in the government service. He didn’t want to retire as he felt he still had a great deal to offer, but he did so with some relief. He believed that research to support industry should do more than merely service its current problems. Research should anticipate problems, identify opportunities, and keep abreast or ahead of international competition. However, he considered that the role of a Director was progressively being reduced to one involving a series of budgetary decisions rather than one providing strategic scientific guidance aimed at addressing national or commercial needs.

Indeed, New Zealand government science went through an extraordinarily frustrating period from the mid 1970s through to the 1990s. There was “user-pays”, the Probine Report, the Beattie report, the STAC report and ultimately the creation of the Crown Research Institutes. For a long-serving member of DSIR such as Ted, this proved to be a distressing time. Ted was a strong proponent of the importance of science and technology and he spent much time reading and writing in its defence, but he became increasingly despairing of what he described as:

- … the primitive and dogmatic view [of Treasury, with it] slowly winning the day, not so much by logical argument but by financial dogma and blunt assertion … The volume and unyielding nature of Treasury arguments were such that any battle weariness on the part of DSIR and other organisations can perhaps be excused.

In private, he likened Treasury staff to adherents of some fundamental religion accepting no criticism and conceding no alternatives to their views, even in areas where they clearly had no particular insight or competence.

In retirement he undertook a study for the NZ Planning Council on the role of Research and Development in the economy of New Zealand. There were many who considered themselves as “instant experts” on R&D but few were aware of the studies that had been made. His intention was not to provide a series of action points and recommendation but to provide an informed background. He was aware that many in government and industry considered that science was marginally relevant to the needs of the country and that Treasury believed that market pull was fine, whereas technology push was not. It was an uphill battle and he must have wondered whether he could have spent his time more profitably. Looking back in 1992, he wrote:

- When the history of science in this country comes to be written, the six years between 1986 and 1992 will appear barren and traumatic ones – ones principally of discouragement to scientists.

Prospects for horticulture

Both while a DSIR director and then in retirement, Ted was actively involved with research problems underpinning the rapidly developing horticultural industries. He followed the practice of Dr Cunningham and Dr Atkinson in maintaining close contacts with the growers, other industry people and extension officers to develop long-term research relationships that were effective. For many years this was achieved through the workings of the Fruit Research Committee and then subsequently the Fruit Research Council. Research priorities were assessed but he emphasised that more than just immediate problems should be considered. Work could have both practical and theoretical importance and he believed that technological development in the fruit industries was more often through a series of small improvements than major “breakthroughs”. Although solving problems was important, so too was anticipating problems, but he believed that scientists should do more than just this. They should question current and accepted practices in the industry, should broaden horizons (the support he gave to the initiation of kiwifruit breeding programmes is a good example), demolish myths and extend opportunities. Ted envisaged a continuous interplay between researchers and the industry.

These and many other ideas were brought together in a major document Prospects for horticulture: a research viewpoint, largely written while Ted was still a Director but published in 1981 after his retirement. In this he surveyed recent developments in horticulture and indicated the likely future trends. One of the most valuable contributions was the bringing together of statistics on the various components of horticulture. These data were updated in a series of annual publications he prepared with co-authors and this series is now continued in the annual publication FreshFacts. Horticulture continued to expand, both in the value of exports and as a percentage of total agricultural exports and Ted therefore updated his report in 1996 with Future prospects for horticulture: the continuing importance of research. In 1992, he also prepared the report on horticulture for the Science and Technology Expert Panel established by the Ministry of Research, Science and Technology to set priorities for Public Good Science. These various reports demonstrate the value of an experienced scientist and administrator presenting a holistic view of an industry and its needs; the reports are possibly his most significant contribution as a Director.

The Royal Society of New Zealand

Ted was elected to the Fellowship of the Royal Society in 1964 and served the Society in many capacities. He was Chairman of the National Committee for Biological Sciences, 1967-1970; a member of the Council 1970–1973; International Secretary 1974–1978; and ultimately President 1981–1985, succeeding his old university friend, Dick Dell. During his term as President, he made a special effort to develop closer links with the Hon. Dr Ian Shearer, the then Minister of Science and Technology. Dr Shearer and Ted were keen to make business leaders more aware of the potential contribution of science and technology to the national economy and also of the contributions that the Royal Society might make. Ted also represented the Society at numerous meetings overseas: in September 1972, he was the New Zealand representative at the General Assembly of the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) at Helsinki, Finland; in September 1976, he attended at the General Assembly of the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS) in Bangalore, India and then a month later at the General Assembly of ICSU in Washington, DC, USA; in 1981, he was member of a delegation to Japan led by the Minister of Science; and in 1983, 1984 he was New Zealand representative at meetings of the Commonwealth Science Council Expert Group.

His most satisfying trip overseas was in May 1974, when Ted was member of a delegation from the Royal Society of New Zealand visiting China at the invitation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. At that time, China was hesitantly emerging from the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution. The invitation to New Zealand was one of the first moves made by the Chinese to re-establish contacts with Western scientific organisations. Today, visits to China are considered routine, but in 1974, this scientific delegation was probably the first-ever from New Zealand to visit China. The trip was very successful and led to a return delegation from China later that year. While in China, Ted had tried to make contact with Professor Li Lairong (Lai Yung Li), who had worked at Mt Albert during World War II after his voyage home from the United States had been diverted by the bombing of Pearl Harbour. Ted had met Li Lairong at Mt Albert while on leave. These attempts were unsuccessful. Ted persisted in his attempts to make contact and in 1975 wrote to Professor Li and received in return a batch of kiwifruit seed, almost certainly the first to come into New Zealand since the original introduction of seed in 1904.

In 1978, DSIR, with the knowledge of the Royal Society, invited a delegation of botanists and horticulturists to visit New Zealand. The delegation came in 1979 and was led by Professor Li. He obviously had a productive and enjoyable time in New Zealand renewing old friendships of nearly 40 years earlier and his charm and his genial personality won him many new friends. In recognition of his professional achievements and the contributions he made to improving contacts between scientists in China and New Zealand, Dr Li was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1979. In turn, Ted was appointed in 1980 as a Guest Member, Academic Advisory Committee, Fukien (Fujian) Institute of Subtropical Botany, China.

The University of Auckland

Ted worked hard to foster the links between DSIR and the University of Auckland. He gave lectures in his specialised field and encouraged other DSIR staff to participate in university teaching and research. He also supervised masterate and doctorate students. For many years, he was an Honorary Lecturer in Botany at the University of Auckland and in 1973 he was appointed an Honorary Professor of Botany, then a relatively rare honour. The University regulations of the time specified that a candidate for an Honorary Professorship should be of not less calibre than a person acceptable for nomination for an Honorary Degree and that he should be internationally distinguished in his field. That Ted was indeed of such calibre was confirmed in 1983 when, at the Convocation celebrating the centenary of the University of Auckland, he received an Honorary Doctorate of Science. The Bollard family remains the only one in the University of Auckland’s history to have had two members of the family receive honorary doctorates, the other being his son Alan (A. E.) Bollard, currently Governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

From 1987 to 1994, Ted was a member of the University of Auckland Council (as Governor-General’s representative and later the Minister of Education’s representative). During that time he served several terms as Pro-Chancellor (1989–1991) and he was a founding Director of Auckland Uniservices Ltd, serving on the Board for seven years, 1989–1996. As Pro- Chancellor, he was a key figure involved in the University’s decision to amalgamate four departments (Biochemistry, Botany, Cellular and Molecular Biology and Zoology) to form the current School of Biological Sciences. While a member of Council, he and his fellow Mount Albert Grammar alumni (Dick Matthews, Bruce (B. G.) Biggs, Sir Keith Sinclair and others) were influential in decision-making both locally and nationally. This Mt Albert Grammar team became known (in some University of Auckland circles) as the Mt Albert Grammar mafia.

Other activities in retirement

“Retirement” saw Ted continue some activities he had accepted while still employed: Member, Council of the National Museum, 1973–1992; Committee member, New Zealand Fertiliser Manufacturers’ Research Association, 1978–1986; and Chairman, Viticultural and Oenological Research Committee (VORAC), 1980–1985. He also took on many new responsibilities including: Member of the Council, University of Auckland; Chairman of the Advisory Committee, Fertilizer and Lime Research Centre, Massey University, 1984–1991; Chairman of a Committee to review Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, 1985; Chairman of the Ministry of Education Working Party on Research and Scholarship, Learning for Life, 1989. He undertook these tasks not because of any emolument – he seldom received more than travel expenses – but from a sense of duty that he should use his talents for the public good.

Ted also became involved in the allocation of research funds from the University Grants Committee – Research Committee, 1981–1989; the Lottery Science Research Committee, 1982–1991 (including a period as Chairman, 1988–1991); the Lottery Science Research Centres Sub-committee, 1990–1993; and as Science Adviser to the Agricultural and Marketing Research and Development Trust (AGMARDT), 1991–1994. His breadth of knowledge and his intellectual curiosity made him an ideal grants assessor; he was genuinely interested in ideas and projects well outside his own expertise. During his time on the University Grants Committee he derived much satisfaction from being able to bring different institutions together to jointly apply for very large items of equipment, which none could hope to purchase alone. On the Lottery Science Committee he was a very efficient chairman, skilfully progressing the meetings through very large numbers of applications, ever courteous, never imperious, although he did admit that some applicants were probably surprised to be successful after he had subjected them to probing interrogation.

Late in life he became fascinated by computers, not just as a way of maintaining contact with grandchildren. He regularly attended the meetings of the Auckland SeniorNet and became one of their best tutors.

Awards and honours

Ted received many awards and honours in recognition of his work: Honorary Lecturer, Department of Botany, 1950–1973; Harkness Fellowship (Cornell University) 1956–1957; Research Medal, New Zealand Association of Scientists, 1958; Fellowship, Royal Society of New Zealand, 1964; Hudson Lecturer, Wellington Branch, Royal Society of New Zealand, 1969; Hector Medal, Royal Society of New Zealand, 1972; Archey Lecturer, Auckland Institute, 1974; Silver Jubilee Medal, 1977; Fellowship, New Zealand Institute of Chemistry, 1967, Honorary Fellow, 1982; Honorary Professor in Department of Botany, University of Auckland, 1973–1985; Doctor of Science, honoris causa, University of Auckland, 1983 at the Centenary Convocation; CBE for services to science, 1983.

Personal interests and hobbies

Only those who knew Ted well were aware of his enthusiasm for Shakespeare. This originated from his first year at Mt Albert Grammar, with one class a week being devoted to Shakespeare. In 1937, when he was in Form 6B, he won the form prize, a copy of the 1927 edition of the Kingsway Shakespeare, a volume which included the complete dramatic and poetic works. This handsome leather-bound volume now shows the sign of much use. Ted saw his first professional production while at Cambridge. He kept the programmes for most performances and managed over the years to hear an enviable list of actors including Dame Sybil Thorndike, Lewis Casson, Leo McKern, Paul Scofield, Peggy Ashcroft and Lisa Harrow (daughter of Ken Harrow, with whom he had worked at Mt Albert). Back in New Zealand he attended performances whenever available and attended a number of adult education classes on Shakespeare and other Elizabethan authors. Ted’s meticulous attention to detail is shown by his having a Shakespeare glossary and reading a play with this at hand, adding the new words he did not know. In this way he built up a personal glossary for each play. What appealed to him about Shakespeare?

- Words! If I were to single out what part of Shakespeare’s genius most appeals to me I would say his way with words: the way in which he selected words, invented phrases and [that] were all together in a coherent whole.

One of his favourite plays was Hamlet and it was fitting that there was a reading from Hamlet at his funeral.

He also prepared a more general list of more than 1300 words that he had found when reading to be of uncertain meaning. In his own writing, Ted was always careful to use words precisely and carefully. He was therefore shocked that accompanying the changes in science policy was the adoption of a whole new array of jargon, peculiar to New Zealand, to describe scientific and technological activities. Indeed, a 47-page glossary was published by the Ministry of Research, Science and Technology to define the terms they used. Ted felt the introduction of a little plain English would have been more helpful.

Another of Ted’s great personal interests was music. This interest seems to have developed during his period with the Army in Italy. Included amongst his books on music is an Army Education Welfare Service publication Rudiments of Music: Study Course which published early in 1945. In his war diary, he lists many of the concerts that he attended in Naples and other opera houses.

- The opera we saw was Puccini’s ‘La Boheme’. It was the first grand opera I’d ever seen and although there was a lot about it that I did not understand or appreciate, I thoroughly enjoyed the whole thing. (Diary, 31 March 1944)

Other operas soon followed:

- Opera ‘Carmen’ was glorious … Am not going to describe opera – I hope the impressions left will be permanent. (Diary, 17 April 1944).

- Saw ‘Tosca’ – enjoyed whole show very much. Am now quite an opera fan. (Diary, 2 May 1944).

- Saw ‘Il Trovatore’ – really marvellous – never enjoyed a single entertainment so much before. (Diary, 2 September 1944)

In all he attended at least seventeen opera performances during his time in Italy, hearing some operas three times, as well as going to orchestral concerts. As was typical, he approached music in a very methodical way, eventually building up a collection of some 50 books on music analysis including many volumes of The New Oxford History of Music and of the New Grove and he also attended courses on music at the University of Auckland. His favourite composers were Mozart, Beethoven and Haydn. He also had a large collection of records and compact discs. His enjoyment of music was encouraged by his wife, Connie, who was a very competent violinist and viola player, playing for some years in the Auckland String Players. Ted himself played the clarinet.

Ted also had an interest in sport and as a younger man had played both rugby and cricket. He would often listen to the radio commentaries on the New Zealand cricket teams, especially when they played overseas. In 1962 he was invited to go yachting with a friend and he enjoyed it so much that, after consultations with Jack Brook, then Director of Auckland Industrial Development Division, he bought a yacht, Valezina. He then spent much of the winters on maintenance and the summers in sailing. His team even managed to win the Yacht Squadron 5th Division racing trophy one year.

Family

In 1946 Ted had met Connie (Constance) Esmond who was taking a mycology class organised by his PhD supervisor. The relationship developed, they were engaged in April 1947 and married in December of that year. Dick Matthews was the best man and the bride wore a dress made from the silk salvaged from parachutes. Connie completed her degree in biology and trained as a teacher. On coming to New Zealand, they had three children and then, when they were all at school, Connie joined Avondale College as a teacher of biology. She was a strong-minded, independent woman with a reputation as a very competent and much appreciated teacher. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1959 but continued with increasing difficulty looking after the family and teaching until shortly before her death in early 1971. This was clearly a tough time for them all.

Ted was proud of the achievements of their three children, Anne, Alan and Richard and of his grandchildren, all of whom completed university studies. It was a special satisfaction for him that on his last trip to England in 2004, he was able to visit two of them who were studying at Cambridge. In 1972 Ted married Joy Cook and they were together for nearly 40 years.

Valedictory

As a young person, Ted experienced life in the raw and also at its most brutal during the time of the Second World War. Yet he brought to his scientific career both a personality and personal strengths that many of his students and colleagues have subsequently strived to emulate. Ted was modest, honest, patriotic and respectful of scientific learning and scholarly ability. But he was also able to recognise the pompous and ridiculous, particularly when these features were displayed by those occupying important positions in academia and science. To those who did not know him, he could appear austere, indeed forbidding, but this was largely due to his innate shyness. Although he might often seem rather intimidating, he was a very good listener, and he appreciated that in others. For us both he was a respected mentor and a trusted confidante, but he was much more than that, he was a friend.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joy Bollard and Anne, Alan and Richard Bollard for letting us read and quote from Ted’s diaries and autobiographical notes. We also thank Jessica Beever, Rod Bieleski and Ron Davison for comments. We acknowledge the insights provided by the paper by Willie Smith (2008) “Dr E.G. Bollard – people, structures and science in New Zealand horticulture.” New Zealand Science Review 65(4): 74–76.

A. R. Ferguson FRSNZ

A. R. Bellamy FRSNZ

Publications

Plant pathology and mycology

Bollard, E. G. 1950: Studies on the genus Mastigosporium. I. General account of the species and their host ranges. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 33: 250–264.

Bollard, E. G. 1950: Studies on the genus Mastigosporium. II. Parasitism. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 33: 265–275.

Bollard, E. G.; Matthews, R .E. F. 1966: The physiology of parasitic disease. Pp. 417–550 in: Steward, F. C. ed. Plant Physiology Vol. 4B, New York, Academic Press.

Beever, R. E.; Bollard, E. G. 1970: The nature of the stimulation of fungal growth by potato extract. Journal of General Microbiology 60: 273–279.

Plant nutrition and orchard management

Atkinson, J. D.; Bollard, E. G. 1953: Note on manganese deficiency in apple, plum and quince. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A35: 19–21.

Bollard, E. G. 1953: Manganese deficiency of apricots. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A34: 471–472.

Bollard, E. G. 1953: Zinc deficiency in pears. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A34: 548–550.

Bollard, E. G. 1953: Zinc deficiency in peaches and nectarines. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A35: 15–18.

Bollard, E. G. 1953: Severe potash deficiency in young apple trees. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A35: 39–44.

Bollard, E. G. 1955: Nitrogen and fruit trees. NZ Soil News No. 3: 82–87.

Bollard, E. G. 1953: Note on internal-browning of quince fruits. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A35: 63–64.

Bollard, E. G. 1956: Effect of steam-sterilized soil on growth of replant apple trees. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A38: 412–415.

Bollard, E. G. 1957: Effect of a permanent grass cover on apple-tree yield in the first years after grassing. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A38: 527–532.

Bollard, E.G. 1957: Trace-element deficiencies of fruit crops in New Zealand. New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research Bulletin 115. Wellington, Government Printer.

Bollard, E. G. 1959. Urease, urea and ureides in plants. In: Utilization of nitrogen and its compounds by plants. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology 13: 304-329.

Bollard, E. G. 1966: A comparative study of the ability of organic nitrogenous compounds to serve as sole sources of nitrogen for the growth of plants. Plant & Soil 25: 153–166.

Bollard, E. G. 1970: The toxicity of L-amino acids to higher plants. Unpublished working papers, Australian Plant Nutrition Conference, Mount Gambier, South Australia, September 1970 2(b): 15–18.

Bollard, E. G. 1971: Problems of fractionating tissue calcium. Unpublished working papers, Australian Plant Nutrition Conference, Mount Gambier, South Australia, September 1970 4(a): 19–21.

Bollard, E. G.; Ashwin, P. M.; McGrath, H. J. W. 1962: Leaf analysis in the assessment of nutritional status of apple trees. I. The variation in leaf nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium with fertiliser treatment, within seasons and between seasons. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 5: 373–383.

Bollard, E. G.; Hurst, A. F.; McGrath, H. J. W. 1962: Leaf analysis in the assessment of nutritional status of apple trees. II. The variation in leaf nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and calcium content between commercial orchards. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 5: 383–388.

Bollard, E. G.; Butler, G. W. 1966: Mineral nutrition of plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 17: 77–112.

Bollard, E. G. 1983: Involvement of unusual elements in plant growth and nutrition, Pp. 695–744 in Läuchli, A.; Bieleski, R. L., eds., Inorganic Plant Nutrition. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology NS 15B, Berlin, Springer-Verlag.

Bollard, E. G. 1991: A review of some aspects of the nutrition of kiwifruit. Report prepared for the New Zealand Kiwifruit Marketing Board.

Bollard, E. G. 1992: The problem of kiwifruit nutrition: a report on a scientific discussion. NZ Kiwifruit February No. 86: 23–24.

Bollard, E. G.; Cook, A. R. 1968: Regulation of urease in a higher plant. Life Sciences 7: 1091–1094.

Bollard, E. G.; Cook, A. R.; Turner, N. A. 1968: Urea as sole source of nitrogen for plant growth. I. The development of urease activity in Spirodela oligorrhiza. Planta 83: 1–12.

Ferguson, A. R.; Bollard, E. G. 1969: Nitrogen metabolism of Spirodela oligorrhiza. I. Utilization of ammonium, nitrate and nitrite. Planta 88: 344–352.

Ferguson, I. B.; Turner, N. A.; Bollard, E. G. 1980: Problems in fractionating calcium in plant tissue. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 31: 7–14.

Tiller, L. W.; Roberts, H. S.; Bollard, E. G. 1959: The Appleby experiments: a series of fertiliser and cool-storage trials with apples in the Nelson district, New Zealand. New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research Bulletin 129. Wellington, Government Printer.

Xylem sap and nutrient translocation

Bollard, E. G. 1953: Nitrogen metabolism of apple trees. Nature 171: 571.

Bollard, E. G. 1953: The use of tracheal sap in the study of apple-tree nutrition. Journal of Experimental Botany 4: 363–368.

Bollard, E. G. 1956: Nitrogenous compounds in plant xylem sap. Nature 178: 1189–1190.

Bollard, E. G. 1957: Composition of the nitrogen fraction of apple tracheal sap. Australian Journal of Biological Science 10: 279–287.

Bollard, E. G. 1957: Nitrogenous compounds in tracheal sap of woody members of the family Rosaceae. Australian Journal of Biological Science 10: 288–291.

Bollard, E. G. 1957: Translocation of organic nitrogen in the xylem. Australian Journal of Biological Science 10: 292–301.

Bollard, E. G. 1958: Nitrogenous constituents of tree xylem sap. Pp. 83–93 in: Thimann, K. V. ed., The Physiology of Forest Trees. New York, Ronald Press.

Bollard, E. G. 1960: Transport in the xylem. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 11: 141–166.

Ferguson, I. B.; Bollard, E. G. 1976: The movement of calcium in germinating pea seeds. Annals of Botany 40: 1047–1055.

Ferguson, I. B.; Bollard, E. G. 1976. The movement of calcium in woody stems. Annals of Botany 40: 1057–1065.

Hill-Cottingham, D. G.; Bollard, E. G. 1965: Chemical changes in apple tree tissues following applications of fertiliser nitrogen. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 8: 778–787.

Plant growth and development

Bollard, E. G. 1961: Growth requirements of plants and plant tissues. New Zealand Science Review 19: 87, 89–91, 105–108.

Bollard, E. G. 1970: Progress in our understanding of plant growth. Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand, General 2: 159–171.

Bollard, E. G. 1970: The physiology and nutrition of developing fruits. Pp. 387–425 in Hulme, A.C. ed. The Biochemistry of Fruits and their Products. London, Academic Press.

Letham, D. S.; Bollard, E. G: 1961: Stimulants of cell division in developing fruits. Nature 191: 1119–1120.

Mark, G. E.; Bollard, E. G. 1962: The stimulants required by several plant tissues for growth in sterile culture. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 5: 360–363.

Sutcliffe, J. F.; Bollard, E. G.; Steward, F. C. 1960: The incorporation of 14C into the protein of particles isolated from plant cells. Journal of Experimental Botany 11: 151–166.

Development of New Zealand horticulture.

Bellamy, A. R.; Bollard, E. G. 1990: Improvement of apple varieties, with reference to the potential role of molecular biology. Unpublished report for New Zealand Apple and Pear Marketing Board.

Bollard, E. G. 1981: Prospects for horticulture: a research viewpoint. New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. Discussion paper No 6. Wellington, New Zealand, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.

Bollard, E. G. 1982: Mapping the future for horticulture. New Zealand Agricultural Science 16: 9–11.

Bollard, E. G. 1982: The development of horticultural exports to Japan. Trade Fair Seminar, 20 June, 1982, Auckland: 72–74.

Bollard, E. G. 1983: New Zealand’s horticulture industry and the role of plant breeding. Pp. 73–82. In: Wratt, G. S.; Smith, H. C., eds. Plant Breeding in New Zealand. Wellington, Butterworths/DSIR.

Boaard, E. G. 1984. Prospects for horticulture. (Consultant’s report). P. 18 in: Horticultural Industries Limited Prospectus for an Issue of Ordinary Shares and Options.

Bollard, E. G. 1985: Fruit and vegetable production in New Zealand. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society of New Zealand 10: 5–12.

Bollard, E. [G.] 1986. The role of science in horticulture. Growing Today 4(3): 14–16.

Bollard, E. G. 1988. Quality in kiwifruit: the need for research. Report for the New Zealand Kiwifruit Marketing Board.

Bollard, E. G. [undated, but known to be 1992]: Horticultural production and management. Output 7. Priority setting for public good science. Report prepared for the Science and Technology Expert Panel, Ministry of Research, Science and Technology.

Bollard, E. G.; Weston, G. C. 1983: Statistics of New Zealand’s horticultural exports to 1982. Special Supplement inserted in Southern Horticulture No 7.

Ferguson, A. R.; Bollard, E. G. 1990: Domestication of the kiwifruit. Pp. 165–246 + 3 plates in:Warrington, I. J.; Weston, G. C., eds. Kiwifruit: Science and Management. Auckland, Ray Richards Publisher in association with the New Zealand Society for Horticultural Science.

Halsted, J. V.; Bollard, E. G. 1986: Statistics of New Zealand’s horticultural exports: year ended June 30, 1986. The Orchardist of New Zealand 59(11): 443–446. Reprinted with some corrections The Orchardist of New Zealand 60(2): 62–63.

Bollard, E. G. 1996: Future prospects for horticulture: the continuing importance of research. [Auckland] : HortResearch on behalf of the author and the New Zealand Fruitgrowers Charitable Trust.

Weston, G. C.; Bollard, E. G. 1983: Statistics of New Zealand’s horticultural exports: year ended June 30, 1983. Southern Horticulture No 12: 62–64.

Weston, G. C.; Bollard, E. G. 1984: Statistics of New Zealand’s horticultural exports: year ended June 30, 1984. Southern Horticulture No 17: 60–64.

Weston, G. C.; Bollard, E. G. 1985: Statistics of New Zealand’s horticultural exports: year ended June 30, 1985. Southern Horticulture No 22: 56–60.

Research in New Zealand

Bollard, E. G.; Dell, R. K.; Collins, E. R.; de Lisle, J. F.; O’Brien, B. J.; Prior, I. A. M.; Petersen, G. B. with Corballis, M. C.; Bollard, A. E.; Gregory, J. G. 1985: The threat of nuclear war: a New Zealand perspective. Royal Society of New Zealand Miscellaneous Series 11.

Bollard, E. G. 1986: Science and technology in New Zealand: opportunity for the future. Wellington, New Zealand National Research Advisory Council.

Bollard, E. G. 1986. Highlights from science and technology in New Zealand: opportunity for the future. Wellington, New Zealand National Research Advisory Council.

Bollard, E. G. 1988: The role of science and technology. NZI Bank. Investor Report, March 1988.

Bollard, E. G. 1988: The effective application of R & D on our economic and social development: what are the obstacles? New Zealand Science Review 45(1-3): 20–25.

Bollard, E. G. 1992: NZ government research: past and present. New Zealand Science Review 49(2): 32–36.

Probine, M. C.; Berthhold, T. M.; Bollard, E. G.; Butler., G. W.; Elliott, R. E. W.; Homewood, D. E.; Waters, T. N. M. 1984: Report on science and technology policy formation. Report to Minister of Science and Technology [unpublished report].

Obituaries

Bollard, E. G. 1988–1990: John Dunstan Atkinson. Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand 1988–90: 20–27.

Bollard, E. G. 1995: Richard Ellis Ford Matthews, 1921–1995. Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand 1991–95: 97–105.

Bollard, E. G. 2010: ‘Atkinson, John Dunstan – Biography.’ from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encylopedia of New Zealand, updated 1-Sep-10. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/5a24/1

Bollard, E. G. 1995: R. E. F. Matthews ONZ, FRS, FRSNZ, MSc (NZ), PhD, DSc (Camb.). New Zealand Science Review 52(3-4): 91–92.

Connor, H. E.; Bollard, E. G. 2012: Eric John Godley. Online at royalsociety.org.nz

Obituary was lodged on website on Monday, 9 July 2012.